Last weekend, I bought myself McVitie’s chocolate biscuits for the first in five years. It’s not that I don’t buy biscuits (Gingernuts all day, everyday please). Rather I can’t bring myself to relinquish the saving of 20p made by opting for Sainsbury’s own, slightly shittier version. I’m the girl that spends an entire month’s salary on a pair of silk slippers, but refuses to spend £2.50 on a pack of feta when ‘greek salad cheese’ comes in 38p cheaper. I wasn’t always like this of course; it’s the final eating disorder residue trickling slowly out of my psyche. Despite my successful recovery, I still find it hard to prioritise food, money-wise. But I’m trying to change things. So, last week, I went on a mad one and bought McVitie’s. And if I wanted to continue with my extravagant lifestyle – swapping cocoa snaps for cocoa pops, buying that really thick, cream-like milk with the literal gold-coloured lid (!) – I could easily do so. I earn a decent salary, I own my flat and I know that, should I spend all my expendable income on decadent dairy products, there’d be several long-suffering loved-ones who would step in if I was caught short.

But for the 14.3 million people in the UK living on the breadline, a situation like mine is a pipe-dream fantasy. And this group is in fact up to two and a half times more likely than middle-class me to become mentally ill. What if your commitment to recovery is willing you to stock up on between-meal snacks, but you simply can’t afford them? As we now know, the stereotype of white, rich, able-bodied woman is a load of old bull. But in all the years I’ve been signposting readers to resources, I’ve yet to come across anything that acknowledges the actual costs of recovery. A 2017 PWC and Beat report found that roughly one in five sufferers incur significant costs as a direct result of their eating disorder.

On average, the illness costs roughly £9,500 per year for those over 20. Over the course of a lifetime, sufferers of long-term EDs are about £45K worse off than healthy people. ‘You can be living in poverty and not be able to eat much but still develop, and cope with, an eating disorder,’ says 50 year-old Tina McDuff from Dundee who developed anorexia and bulimia at just 13, whilst living off food vouchers provided by the local council. ‘I had two younger sisters and my priority was always to make sure they ate so I’d give them my vouchers. Or I’d exchange them for cigarettes or diet coke. I didn’t even know I had an eating disorder, I just knew I didn’t want to eat.’ Seven years later, following an inpatient admission, she found herself living in a hostel and suddenly tasked with buying herself food. The illness had left her unemployed and solely reliant on benefits. She says: ‘I was in an inpatient unit and then a rehabilitation facility where nurses would take care of all my food. All of a sudden I was left to fend for myself with little to no money and I had no idea where to start.’ Tina’s outpatient care team would take her to Iceland and suggest she opt for the most calorific, cheaper foods. But anyone who has wrestled an eating disorder will know that actively seeking out the most fatty foods available is about as terrifying as it gets.

“I LIVED OFF AERO BARS FOR TWO WEEKS. THEN I DEVELOPED BOILS ALL OVER MY BODY”

‘They’d suggest things like frozen hash browns which were really cheap and calorific, but I wanted to ease myself in with foods that I knew were nutritious. The problem is you can get high calorie foods like frozen pizza for £1 but when you’re early on in recovery most people don’t want to eat that.’ So, for the following two and a half years Tina remained stuck in her ‘highly disordered’ eating patterns, despite her dedication to recovery. She says: ‘There was no support to help me find foods I felt able to eat and could afford so I ended up just living off fruit and vegetables or the odd frozen ready meal. I really wanted to challenge myself, though. I’d always missed Aero chocolate bars when I was unwell so I wanted to treat myself to them. I worked out that I could afford to just live off four or five of the small bars each day. I did that for a few weeks until I started developing boils all over my body. I thought I was doing well by giving into a craving.’ To make matters worse, Tina had grown up vegetarian. And with no cookery knowledge, her options were bleak.

‘I remember going to town and looking around the shop and thinking there was nothing. I didn’t know how to make anything and I couldn’t afford anything I felt comfortable eating. I could never have justified spending £5 on one thing, and sometimes I couldn’t even afford to turn the oven on or use the hob.’ Food and electricity aren’t the only costs of recovery. Bryony, who even struggled to ‘make ends meet’ during her stint in hospital, wasn’t prepared for the extras she’d have to fork out for when discharge came around. ‘I struggled with buying new clothes and my own medication because my benefits didn’t cover that cost,’ says the 23 year-old. ‘I ended up having to take out loans because my recovery meant I needed things my means didn’t stretch to.’ For Tina, with the help of her mental health care team, she eventually grew comfortable with baked potatoes and beans, helping to maintain her weight at a just-about healthy level. Two years later she got a job working with her father’s bar and club business – a game-changer for her recovery.

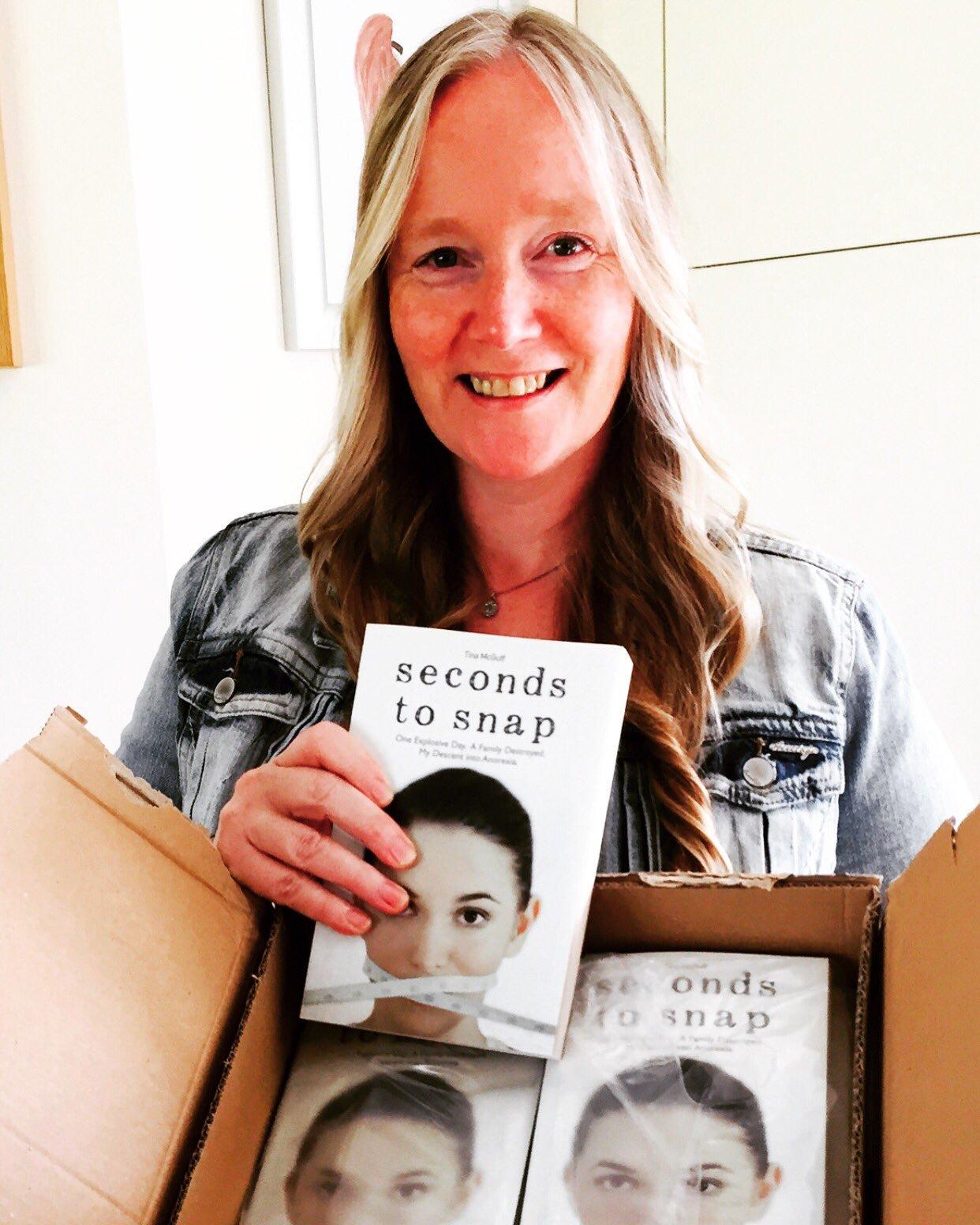

Tina now, almost four decades after her eating disorder began

Tina now, almost four decades after her eating disorder began

‘My life suddenly turned around,’ she says. ‘I could suddenly buy all these things that I could never afford before but it soon became an obsession with “healthy” foods, so everything had to be nutritious or organic.’ It’s been a long slog for Tina. It was only when she reached 30-something that she says she finally felt ‘free’. ‘I’d recovered but I still lived a very regimented life, getting up at 5am to swim every day and only eating so-called “healthy” foods. But one day I realised I was so exhausted of it all and thought, “fuck it”. I bought a tub of Haagen Daaz, ate the whole tub, and haven’t looked back since.’ It wasn’t just the calorie content that made Tina’s indulgence such a milestone. It was the price, too. She says: ‘I’d always seen Haagen Daaz as a luxury because it was so expensive. It was my biggest ever extravagance. I was in a phenomenal, happy time in my life and I remember feeling that I’d had enough of living this “perfect” life. I ate the whole thing and didn’t care a jot.’ Would this moment have come sooner had she been more, shall we say, ‘comfortable’? ‘Absolutely,’ she says, ‘. If money wasn’t an object, recovery would have come much quicker. It was one of the biggest obstacles.’ Tina may have stumbled on her lucky break, but for most people, that longed-for day when everything changes forever will never come. So what of someone like Bryony, who can’t afford the ‘challenging’ lasagnes that her fellow patients eat on a weekend break from hospital? Well, there are a significant number of financial benefits you may well qualify for – you’ll find an extensive list here. Citizens advice and Beat can help too.

Otherwise, don’t be afraid to speak with a dietitian, psychiatrist or GP about your financial situation and how that will inevitably affect recovery. Tina, who now mentors other sufferers and has written a book about her illness called seconds to snap, advises: ‘There are food banks available for people who are really struggling but it can be difficult because it’s usually not the most nutritious foods, it’s just about tying you over. ‘If you’re recovering from an eating disorder, that can be overwhelming. Jack Monroe has great recipes on how to get a hearty meal for not a lot of money. Potatoes are a good staple but some find them intimidating. Some people feel more comfortable with sweet potatoes to begin with.’

My advice? Remember that we can all only do our best within the personal limits we’re handed. Even with all the money in the world, recovery can feel like uphill torture. If your means are limited, the battle is likely to be bloodier still. Don’t beat yourself up. Do what you can do, and when you can’t, ask for help. And if, like me, you can afford it but can’t bring yourself to buy it, spare a minute to think of Tina. It might be the motivation you need to put down the sodding, watery, tasteless salad cheese.